How Orthopedic Surgeons Fix Bones - Part 2

⌚️ read time: 4.8 minutes

Let’s continue our ‘how to be an orthopedic surgeon’ series. Unofficially, of course.

A few weeks ago I wrote about primary bone healing and how we use a technique called compression plating to take advantage of this type of healing. You can review that article here.

Today is all about secondary bone healing.

Secondary Bone Healing

As a reminder, bones can heal in two different ways after they break. The primary determinant of how the bones will heal is whether the bone ends remain close together after they break and how stable they are as they try to heal.

As we discussed last time, primary bone healing occurs when the ends of the bones are still touching and are very stable.

Which means secondary bone healing occurs when the ends of the bones are a little further apart (not too far apart or no bone healing will occur) and not quite so stable (but not too unstable or no bone healing will occur).

The maximum amount of instability under which a bone can still manage to heal is 10% strain. Strain, in its simplest form, is a measure of how much a fracture moves relative to its original fracture gap.

Or really just how much those bone ends are wiggling around.

Casting

So you may find it interesting to know that this is how casts work! The cast will provide external stability to your arm or leg while the bone heals.

And when your doctor says you need surgery because a cast isn’t an option?

They’re analyzing multiple factors (how the x-rays look, the fracture pattern of your bone, your health, their years of experience) to effectively GUESS that putting your broken bone in a cast would result in greater than 10% strain…and thus your bone wouldn’t heal right.

Or it wouldn’t heal at all.

If a cast will result in less than 10% strain? Cast away!

Surgery for Secondary Bone Healing

So how do we accomplish secondary bone healing with surgery then?

Recall that primary bone healing works best when there is a single break across a bone. When this occurs, the surgeon can take that crack, line it up, and compress it back together.

But what about other fracture patterns?

Say your bone shattered into multiple pieces? Or is in an area of your body where applying a plate along the length of your fracture would cause a lot of damage (imagine cutting open the entire length of the femur to apply a plate)?

Here is where an orthopedic surgeon can use secondary bone healing to their advantage.

Let me show you a couple ways we accomplish this.

Back to the toolbox

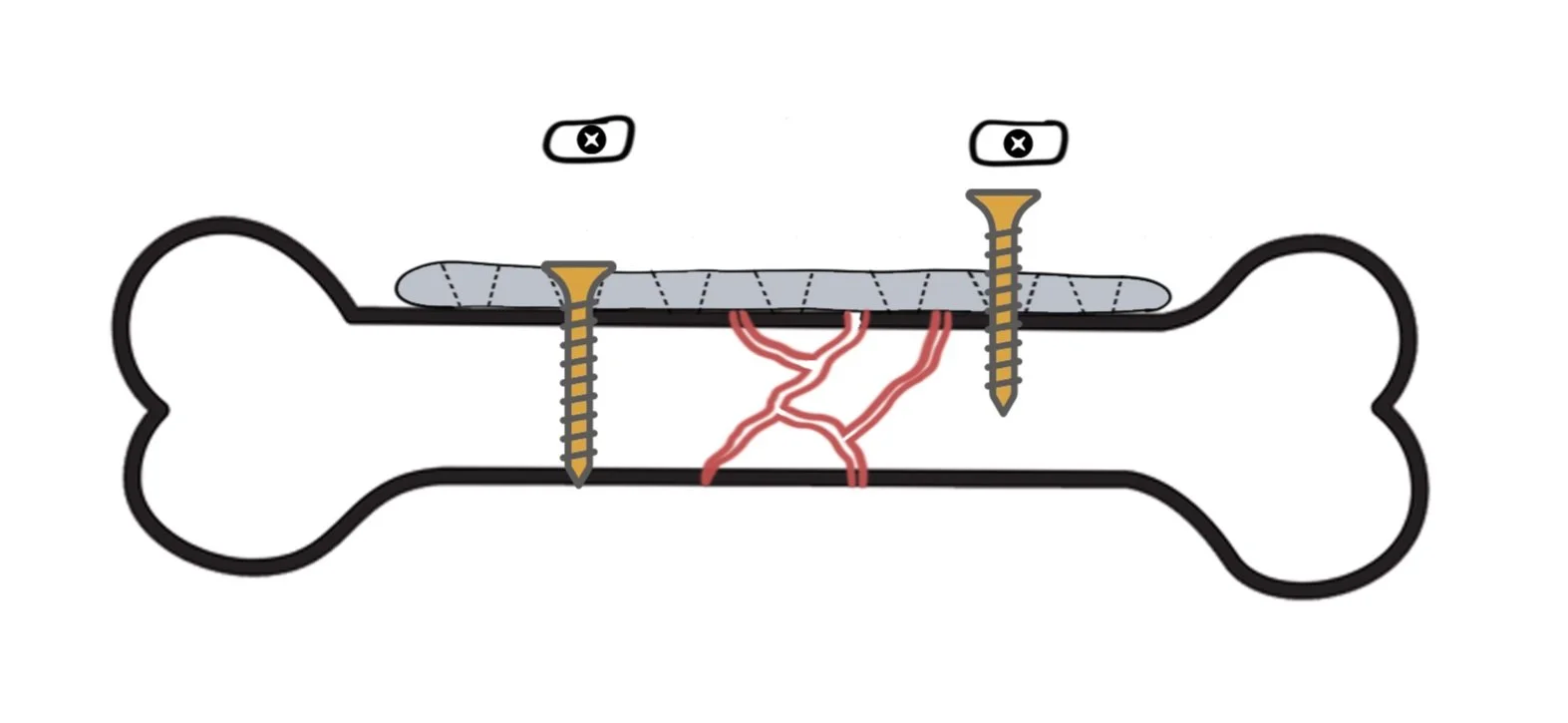

Below is my same cartoon I drew of a fracture. But this time it’s in a lot of shattered bits.

Unlike in our first example a few weeks ago, there’s no way to achieve compression across all those different fracture lines. So we need a different strategy that doesn’t rely on compression.

Enter the bridge plating strategy.

In this technique, we do exactly what it sounds like. On one side of the fracture, we place a screw in the plate. This holds the plate down to the bone for stability.

Then, on the other side of the fracture, we place another screw. But unlike in compression mode where we place that screw in the far side of the plate hole, we simply put this one in the middle.

Thus forming a bridge. Without compression.

As long as the overall architecture of the bone from end to end is correct (meaning one end isn’t rotated or crooked relative to the other), the body will fill in all the cracks.

Like grout.

It does this with an extraordinary tissue called callus.

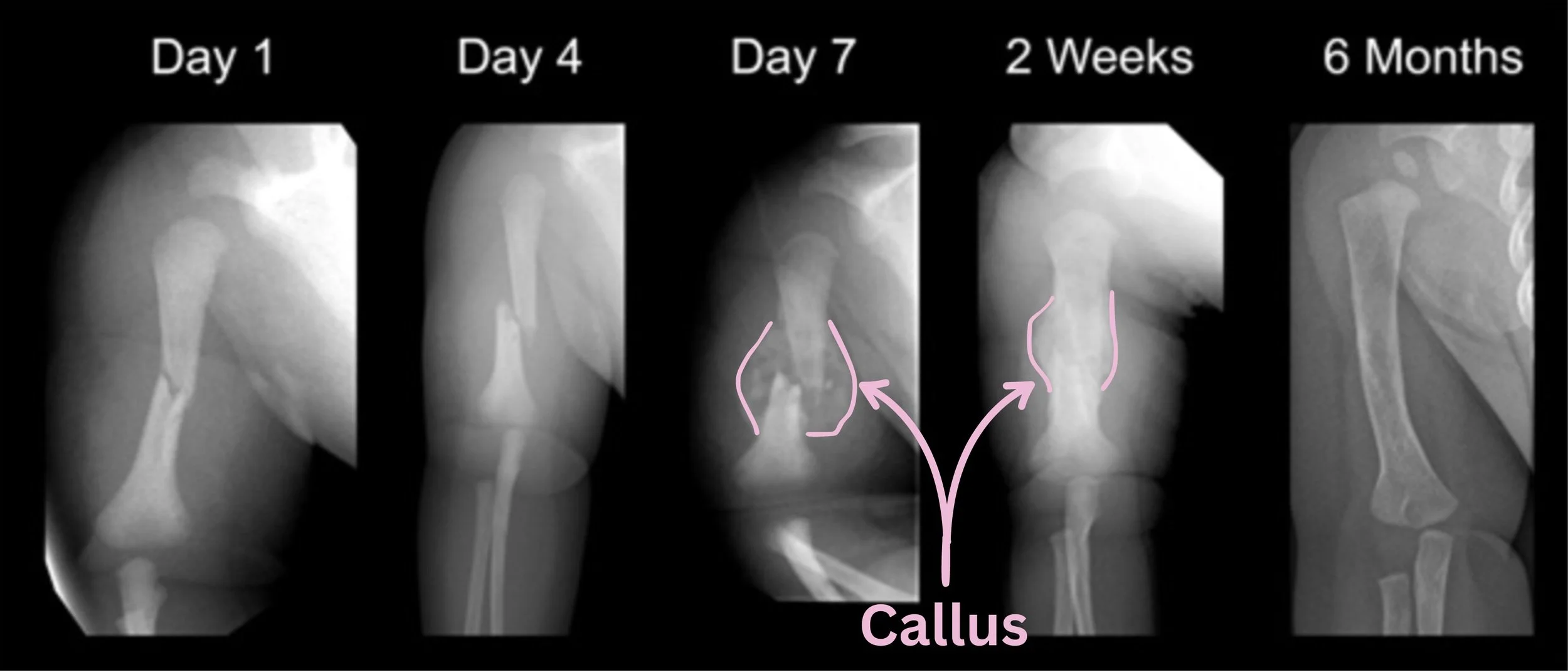

Remember that bones take 6-8 weeks to heal? Well, over the 6-8 weeks after a fracture occurs, the body first lays down clot between the shattered bone ends. That clot then slowly changes to a big hunk of cartilage to provisionally stabilize the bone ends (remember, it wants to decrease the strain so it can heal). And then that cartilage eventually converts to bone.

Check out these images from the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne (with my doodling to show the callus) of a pediatric humerus fracture and its incredible callus remodeling.

Royal Children's Hospital: https://www.rch.org.au/fracture-education/fracture_healing/

Isn’t that awesome?

We use this same concept with bridge plating. We’re essentially providing some reasonable stability so the body can take over the rest of the healing process with callus.

Boom. Fracture healed.

Nailed it

Alright, here’s your bonus lesson.

Remember the example I gave about the femur? Can you imagine opening up the entire length of the femur to place a plate along the whole bone?

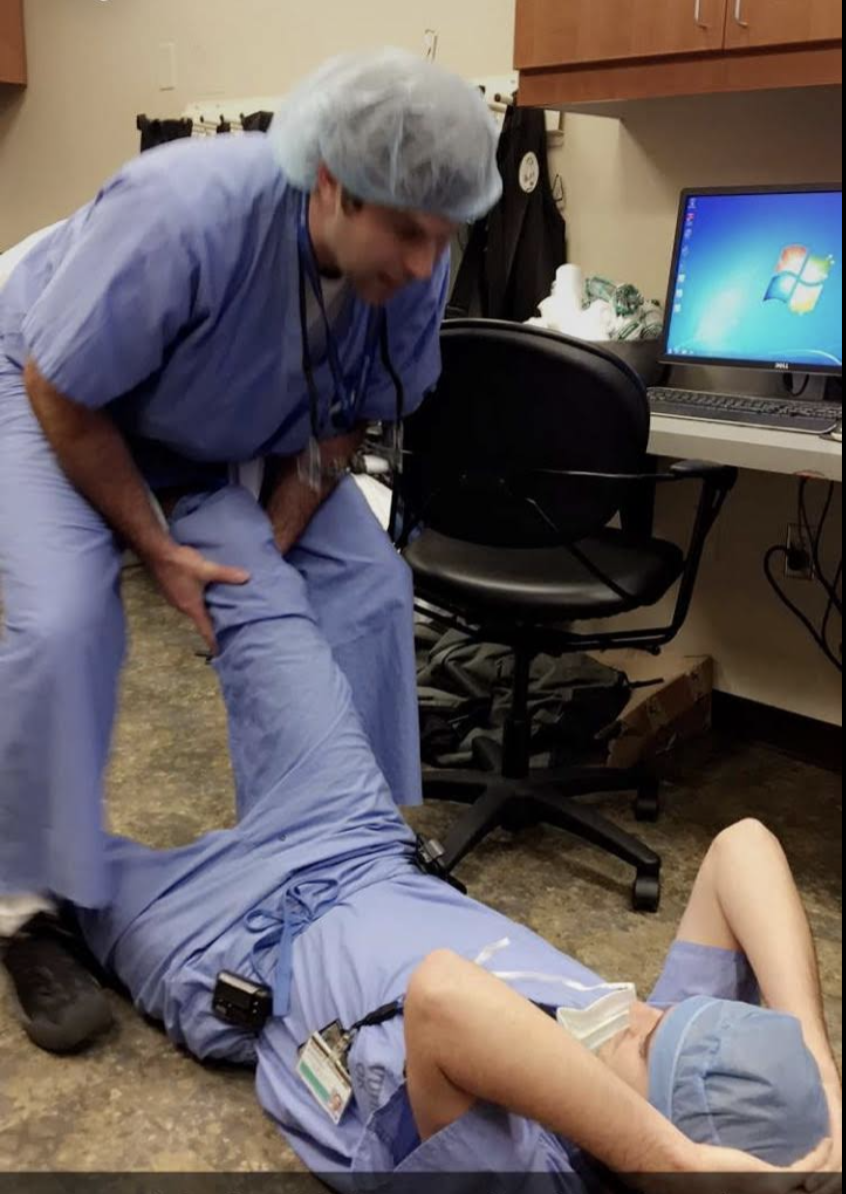

While we sometimes have to do that, the more elegant solution is known as the femoral nail.

In this procedure, we open a small hole at the top of the femur. Because bones are essentially hollow on the inside (imagine a PVC pipe that is hard on the perimeter but hollow inside), once that hole is opened at the top of the femur, we can now slide a long metal NAIL (or rod) down the hollow interior.

As long as we pull really hard on the leg (see image to the right) to line up the overall architecture of the bone (remember, no malrotation and no malangulation), this nail will hold that alignment once secured.

And what happens next?

You got it. Secondary bone healing -> callus -> healed bone in 6-8 weeks.

Voila.

The result

Just like with primary bone healing, this bony healing process usually plays out over the course of about 6-10 weeks following surgery. Similarly, once the bone heals, all that hardware is completely irrelevant. Most patients choose to keep it for life rather than having another surgery.

But its job is complete as soon as the fracture heals.

Takeaways:

When using compression is not an option to fix a bone, orthopedic surgeons can use the phenomenon of secondary bone healing to their advantage

This is typically achieved via bridge plate fixation or the use of an intramedullary nail

But this is also how a standard arm or leg cast works! The key is achieving enough basic stability of the fracture to allow the body to take over the rest of the healing process with a tissue called callus.

So there you go. Now you know what it takes to be an orthopedic surgeon. Just be sure you don’t try any of these at home :).