What Is Cubital Tunnel Syndrome? The Ultimate Patient Guide

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to purchase after clicking a link, I may receive a commission at no extra cost to you.

What is Cubital Tunnel Syndrome?

Welcome back to another article in our series of basic introductions to common hand and upper extremity conditions.

Today we will be exploring a type of peripheral nerve compression we see frequently, known as Cubital Tunnel Syndrome (CuTS for short).

My goal is to teach you all you’d like to know about CuTS as quickly and simply as possible. This is about empowering YOU to take control of your health and your pain. Most patients don’t want all the medical jargon — just simple answers.

Have you ever hit your funny bone? That is what cubital tunnel syndrome feels like!

If you have ever bumped your elbow and “hit your funny bone,” that is the ulnar nerve! When this happens, you directly impact the ulnar nerve at your elbow. Not a great feeling.

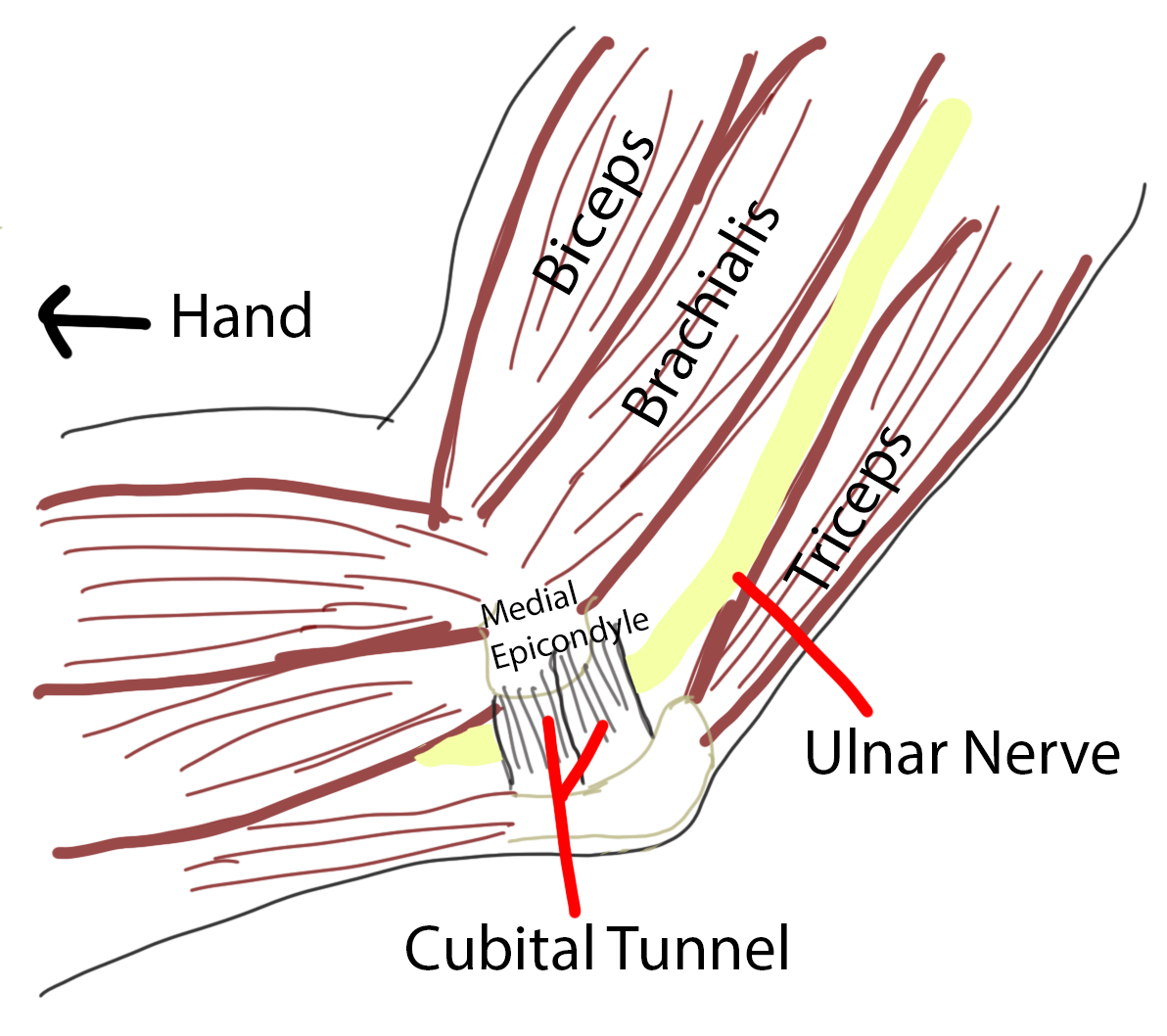

If you feel the bone on the tip of your elbow (olecranon) and the bone on the inside of your elbow (medial epicondyle), the ulnar nerve passes in a groove right between these two bones (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - The ulnar nerve passes between the two bony ‘bumps’ you can feel on your inner elbow

Rather than a direct impact, cubital tunnel syndrome results from compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. If you’ve read my article on carpal tunnel syndrome (here), this may sound familiar. Carpal tunnel syndrome is compression of the median nerve.

Don’t worry about the names of the nerves. Just remember that the median nerve and ulnar nerve are two of the three main nerves that travel from your neck to your hand.

In both cases, the nerves serve two primary functions once they reach your hand:

Allow you to feel objects in your hand and fingers (sense of touch)

Power the muscles of your hand

Specifically, the ulnar nerve begins in the brain and exits your neck to travel down the inside of the upper arm (think armpit). It is actually the only major nerve to travel around the back of the elbow. Remember this for later, as the location of the nerve around the back of your elbow is an important point.

The Pinky Finger Is The Lighthouse Of Cubital Tunnel

So what are the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome?

Specifically in CuTS, you will feel symptoms in the small (pinky) finger and sometimes half of the ring finger. Just like carpal tunnel, the pinky finger is the key!

Cubital tunnel symptoms are similar in character but different in location compared to carpal tunnel. It is common to feel numbness, tingling, burning, or shooting pain. These are typical of nerve symptoms in general.

In carpal tunnel syndrome, the pinky finger is usually the only finger that is not involved; in cubital tunnel syndrome it is often the only finger that is involved. These symptoms are felt both on the palm and back side of the ring and small finger, making it feel like the entire finger is numb.

Similar to carpal tunnel syndrome, cubital tunnel symptoms can be worse at night. But typically the symptoms are more common during the day.

A potentially scary downside of CuTS relates back to the anatomy.

The ulnar nerve is responsible for delivering muscle control to the majority of the muscles in your hand. That means if your cubital tunnel becomes advanced without you noticing (or you ignore it), it can have profound consequences on the function of your hand. As we discussed with carpal tunnel, once your nerve becomes so pinched that your muscles begin to wither away, the associated muscle weakness is almost always permanent.

If you sense any weakness or shrinking of the muscles in the hand (see Figure 2), run (don’t walk) to the nearest hand surgeon.

Figure 2 - This hand has atrophy in the hand between the index and middle finger. Do you see how it appears sunken in? This is a warning sign that the ulnar nerve may be permanently damaged.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome = Ulnar Nerve Compression

As I mentioned above, CuTS results when the ulnar nerve is pinched at the elbow.

Specifically, as the ulnar nerve travels behind the elbow, it passes through a narrow channel we call ‘the cubital tunnel.’

Anatomically, the floor and the walls of the cubital tunnel are made from the bones of your elbow. Over the top, a series of soft tissue bands make up the roof of the cubital tunnel.

Compression can be dynamic (bend your elbow) or static (lean on your elbow)

Compression of a nerve typically comes in two forms. It either is always compressed due to permanent changes in local anatomy, which is a type of compression I would term static. Or, it is only compressed in certain arm positions, a type of compression known as dynamic.

CuTS is typically a result of dynamic ulnar nerve compression.

To demonstrate this, you can actually do a fun experiment on yourself (see Figures below). Put your elbow out completely straight and then grab the skin over the tip of your elbow. Feel how loose this skin is?

Now hold on to that skin while you bend your elbow and feel that skin get extremely tight and thin.

What a difference with elbow positioning, right?

Now think about your nerve. As I mentioned above, your ulnar nerve is the only nerve that goes around the back of your elbow. What you just felt happen to your skin also happens to your nerve any time you bend your elbow past 90 degrees.

Proper elbow positioning during the day is your fastest route to recovery

Maybe now you’re thinking, ‘That’s great and all, but I don’t bend my elbow THAT much…’

Think again….

Do you recognize this position now?

In the 21st century, we spend unnatural lengths of time with our elbows bent. Often for hours at a time.

Meaning our ulnar nerve is being squashed. Constantly.

To make it worse, how do you tend to sleep at night? All curled up! Even if you fall asleep with your arms straight, you are almost guaranteed to curl up your arms for significant portions of your deep sleep stages, yet again compressing your ulnar nerve for hours at a time.

As if that weren’t enough, in addition to positioning, I’d like you to think about direct pressure. The ulnar nerve sits relatively close to the skin on the inside of the elbow. Meaning it is easy to lean on your elbow and directly compress the nerve.

If you find yourself leaning directly on your elbow for prolonged lengths of time (driving with your elbow leaning on the console, working with your elbow on an armchair), you will want to make a concerted effort to avoid this additional compression.

No special tests are needed to diagnose cubital tunnel syndrome

With your new understanding of cubital tunnel syndrome, you may be asking yourself, how is cubital tunnel syndrome actually diagnosed?

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a condition that is diagnosed purely based on ‘clinical history.’

What does that vague term mean?

That means I will typically diagnose you based on the story you tell (What are your symptoms? When do you feel them and where?) and your physical examination.

As I discussed above, symptoms typically include numbness, tingling, burning, or shooting pain that can stretch all the way from the elbow into the ring and small fingers of the hand. Some patients do feel discomfort of their inner elbow as well. Severe cases result in profound hand weakness and shrinking of your hand muscles.

A typical physical examination will include testing for a Tinel sign. In this test, the patient feels a jolt of pain or numbness when tapping a finger along the nerve in the groove at the elbow (essentially recreating ‘hitting your funny bone’). The other most common test is to hold your elbow in full flexion (completely bent) for 45 seconds. If your ring and small fingers go numb while in this position, the test would be considered positive for cubital tunnel syndrome.

As you can see, there really is nothing fancy here — it’s pretty straightforward.

What to know if additional testing is used

If there is doubt about the diagnosis, or when considering surgery, patients may be sent for formal nerve studies (electromyography/nerve conduction). These are typically performed by a neurologist.

The problem with cubital tunnel syndrome comes back to the static vs dynamic compression that we discussed above. Cubital tunnel syndrome is primarily a dynamic condition, meaning that the ulnar nerve is only pinched when the elbow is bent. The nerve tests are not performed in this position, so they oftentimes will show up negative for cubital tunnel syndrome.

Imagine the confusion and angst that causes in my office! It is always a long discussion when a patient comes to me with classic cubital tunnel symptoms and a negative nerve test.

It is important to remember my first point. Cubital tunnel syndrome is a clinical diagnosis - this means no tests are truly required to make the diagnosis. It’s purely based on the story of your symptoms and your exam.

The cornerstone of treatment is knowledge and activity modification

Cubital tunnel tends to be more enjoyable for me to treat (compared to more limited options in carpal tunnel syndrome) because I have an array of options to offer you, depending on how you’re feeling and what your treatment goals entail relative to the severity of your symptoms.

If you’ve read my DeQuervain’s tendinitis articles (here), this will sound familiar. The most important factor in treating cubital tunnel syndrome is knowledge.

What do I mean by that?

Purely knowing what elbow positions cause cubital tunnel syndrome can be the only thing you need to treat it.

I had left-sided cubital tunnel symptoms for years until I went to medical school and learned about the condition. Now I just know to avoid prolonged periods of time in elbow flexion! And within a couple of months of learning this information, my symptoms disappeared. I get a brief flare from time to time when I’m forgetful and I just make the adjustment again. Problem solved.

This treatment strategy would fall in the category of activity modification. Modify your environment so you can resolve your symptoms.

Think about how you spend your day. Identify the times you spend in positions of 90 degrees of elbow bending or more and change them! Typing, texting, eating, reading, watching TV, driving.

Again, knowledge is power. Take back control of your own health.

Nighttime bracing can be the extra boost you need

If you want to step up your treatment a notch, nighttime bracing can be a great option.

As I mentioned above, you essentially cannot avoid spending a significant portion of each night curled up with your elbows completely bent (think the fetal position). This pinches the nerve. All. Night. Long.

And then you wake up and compress it for significant portions of the next day while typing, texting, eating, and reading!

Think of nighttime bracing as free lunch. If you can keep your elbow semi-extended (it doesn’t have to be fully straight), you get all those hours of time when your nerve is healthy and free.

And that’s exactly what the brace does. It prevents you from bending your elbow too far. This can be a more formalized ‘hard’ brace with a shell, similar to a hockey or lacrosse elbow pad. Or it can be much more informal, made from a rolled-up towel and a sleeve. My therapists and I lovingly refer to this as an elbow ‘muff’ (see Figure and steps below):

Start with a sleeve (shown is a stockinette - choose 3 or 4” based on arm size)

Roll up a small white towel and place it in the crook of the elbow

Roll up one side of the stockinette over the towel

Roll the other side of the stockinette over the towel

Wear this to bed — notice how it won’t allow elbow flexion past 90 degrees!

The key is something that is comfortable and prevents bending your elbow. Beyond that, the choice is yours.

Therapy for cubital tunnel syndrome - another option!

You may get different answers depending on who you talk to, but cubital tunnel syndrome is one of those conditions that does seem to have a pretty good response to therapy in many patients. Not all. But it’s often worth the try.

For various reasons, the ulnar nerve is more prone to symptoms if the overall tension of the nerve from neck to fingertips is out of balance. So various stretching exercises and nerve glides can play a large role in recovery. While all our therapists tell me therapy for carpal tunnel is essentially pointless, the majority of them strongly support therapy for cubital tunnel.

Cubital tunnel release surgery = Decompressing the ulnar nerve

As with many conditions, there may become a point when it’s time to consider surgery. Whether your cubital tunnel is advanced and threatening the strength of your hands, or the above treatments just didn’t work, surgery can be very effective for ulnar nerve compression at the elbow.

In this surgery, a small incision is made over the inner elbow, essentially directly over the nerve (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 - The incision for cubital tunnel release is directly over where the nerve is drawn above. Most incisions will be a little shorter than the yellow line drawn here.

In this region, there are a series of bands and ligaments that contribute to ulnar nerve compression, all of which join to make up the roof of the cubital tunnel (see Figure 4). Just as in carpal tunnel syndrome, the roof of this tunnel is divided in surgery so that the nerve can receive its necessary blood supply, nutrients, and oxygen.

Figure 4 - Note the series of ligaments crossing over the nerve to form the cubital tunnel. In cubital tunnel release surgery, these are divided to relieve pressure on the ulnar nerve.

Sometimes it is necessary to perform an ulnar nerve transposition

There is one additional consideration relative to the anatomy.

In about 10% of cases, surgical release of the cubital tunnel actually reveals that the nerve has become unstable in its bony groove. If this is the case, the nerve slips out of the groove between the olecranon and medial epicondyle when the elbow is bent.

This is something we typically can’t predict until after the nerve is decompressed. Occasionally it can be felt in the office before surgery. Oftentimes this is the result of being born with a ‘shallow groove’ or other slight anatomic difference.

The stability of the nerve is always tested during surgery following a decompression. If it is found to be unstable, I will then formally move the nerve to the front of the elbow where it ‘wants to be’. This is called an anterior transposition.

If you need this, it adds about 15 minutes to your surgical time, two additional weeks of activity restrictions, and often requires a brief period of elbow splinting to allow the nerve to stabilize in its new environment before elbow motion begins.

Recovery From Cubital Tunnel Release Surgery

Typical restrictions after a cubital tunnel release surgery will last about a month. Your skin is usually closed with absorbable sutures that do not require removal. If you don’t have an anterior transposition, then I place you in a soft dressing and allow early gentle elbow range of motion. You should avoid heavy lifting or resisted elbow exercises (push-ups, tricep dips) for at least one month.

If you had an anterior transposition, that one month becomes six weeks. And as I mentioned, you will spend the first week or two in a splint, rather than a soft dressing.

Please always remember the goals of surgery

Just as in carpal tunnel syndrome, all I am doing in surgery is decompressing the nerve. That’s it. Once that happens, blood flow is restored to the nerve and it can begin the healing process.

What I don’t control is how your nerve heals. Translation? Unfortunately, I cannot guarantee that your pre-operative symptoms get any better. That is up to your body.

What’s the reality? Most people have a rapid resolution (a few weeks) of their pre-operative painful shooting and burning symptoms. Longstanding numbness takes longer to resolve and in some cases is permanent. As I mentioned above, any weakness or loss of muscles in your hands is typically permanent, even after surgery.

This all boils down to one thing. We do this surgery to prevent the worsening of your symptoms to the point of loss of hand strength and function.

This is how you should think of this surgery when making the decision. Cubital tunnel syndrome is often progressively damaging over time if not managed. Surgery prevents worsening and can ward off permanent nerve damage if done early enough.

Putting it all together

That about does it for our whirlwind tour of cubital tunnel syndrome basics. I hope you come away from this with a new understanding of why your small (pinky) finger goes numb and how you might best manage your symptoms.

Remember. Knowledge is more than half the battle.

Take back control of your own health — I wish you the best of healing.